From the Frontline to the Coastline

- 4DHeritage team

- Jan 22

- 4 min read

Could Humanitarian Innovations Offer Solutions to Communities Threatened by Coastal Erosion?

Where This Began

The starting point was work using drone-based systems to understand glacial retreat in the Alps and rockfall risk on Scottish Highland roads.

Watching how relatively simple aerial surveys could reveal patterns in ice movement or identify unstable rock faces raised a question: if these methods could track environmental change in mountains, what else might they document?

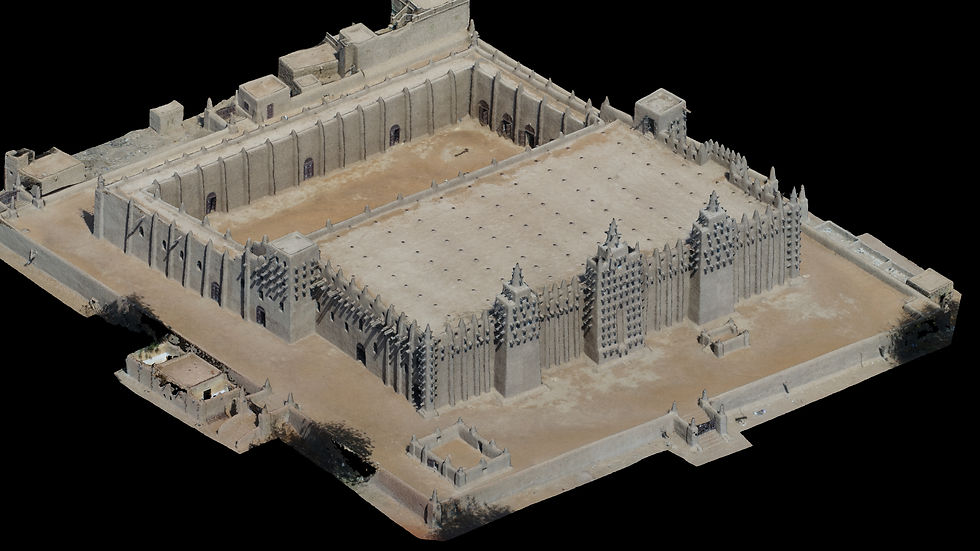

In 2016, an opportunity arose to explore this in Djenné, Mali—a UNESCO World Heritage Site that had become increasingly isolated by regional conflict. Tourism had stopped. International support organisations had largely withdrawn. The local community was watching their architectural heritage deteriorate, with limited resources and few options for documentation or monitoring.

The Humanitarian Innovation Fund provided modest support to test whether affordable consumer drones and community members with basic training could create useful documentation.

The project worked with the local Djenné Manuscript Library, which had been digitising endangered manuscripts since 2009, and MaliMali, a social enterprise that had shifted to online sales when tourism collapsed.

The approach centered on something straightforward: if community members could learn to operate consumer-grade equipment and process the data themselves, they wouldn't need to wait for external experts or expensive professional surveys. They could document what mattered to them, at intervals that made sense locally, and maintain that capacity over time.

What emerged was documentation with centimeter-level accuracy—detailed enough for conservation planning, monitoring change, and making the case to funders. The community trained some of their own people.

The work was presented at international forums. But more importantly, the equipment and skills stayed in Djenné when the project ended.

Since then, similar approaches have been applied in various contexts: conflict zones, remote heritage sites, environmental monitoring in challenging conditions. Each project taught something about what works in different settings, what equipment choices matter, how to transfer skills effectively, and what communities actually need from documentation versus what external organisations think they need. Now the question is whether these experiences—from Mali's conflict zones to Ukraine's environmental monitoring—might have something to offer UK coastal communities watching their landscape change.

The Expertise: Learning Across Different Contexts

Mali (2016-2017)

The initial community documentation project in Djenné focused on creating high-resolution 3D models of endangered heritage sites. The approach combined aerial drone surveys with ground-level smartphone photography from community members. What became clear was that the combination of different data sources—aerial overviews providing context, ground-level detail adding texture—created more useful documentation than either alone. The technical methodology worked, but equally important was learning how to structure training so that local people could continue the work independently.

Zanzibar

Work on coastal heritage sites—caves, palaces, graves—facing both natural erosion and human pressure. The challenge here was different from Mali: very different- some built, others natural heritage spread across the island, tidal variations and journey times affecting access.

Egypt

Archaeological site mapping in desert oases where the interest was understanding how human intervention and climate factors interact to affect fragile landscapes.

The work involved monitoring a conservation programme as part of broader heritage stewardship where water availability, agricultural practices, and tourism development all play roles.

Oman

This was heritage documentation paired with youth training programs. The focus shifted to how you structure learning so younger people can become the next generation of heritage stewards. Questions about which technical skills matter most, how to balance equipment complexity with accessibility, how to connect documentation to conservation planning that communities care about.

.

Ukraine (2022-present):

The RAU Ukraine collaboration with Sumy University was set up to look at the impact of the conflict on agriculture and explore strategies for rehabilation of damgaged agricultural land. The work here is fundamentally about creating records when access is limited, security is uncertain, and the window for documentation may be brief, and training / knowledge transfer.

UK Experience

Thorpeness: During COVID restrictions, when many field projects stopped, there was an opportunity to investigate the sudden appearance of a wreck on Thorpeness beach. The work involved combining aerial imagery with historical maps and tide data to understand what had been revealed and why.

A webinar shared this with a wider audience interested in coastal change. Watching how the beach has continued changing since then—and accelerating—has made the connection between heritage monitoring methods and coastal erosion challenges increasingly apparent.

The value of this local work was in understanding specifically UK coastal conditions: planning requirements, existing monitoring frameworks, how different agencies and community groups interact, and what evidence standards are expected for different purposes (conservation listing, planning applications, engineering assessments, funding bids).

Insights gained

The work across these different contexts has involved learning about:

How and why to document in 3D: When 3D models are actually useful versus when 2D imagery suffices. How to create spatial records that serve multiple purposes—not just pretty visualizations but data that conservationists, engineers, and community members can all use for their different needs.

Topographical analysis and risk assessment: How aerial surveys can inform understanding of risks—whether rockfall on Highland roads, flood patterns in desert oases, or erosion rates on coastlines. What level of accuracy is needed for different decisions, and what can be achieved with different equipment choices.

Community-based approaches: The practical questions of who operates equipment, who processes data, who interprets results. The difference between "community engagement" (asking people what they think) and "community-based" (people doing the work themselves). What training looks like, what equipment choices enable or constrain local operation, how to structure data management so it remains accessible.

The consistent finding across contexts: communities given appropriate tools and straightforward training can generate professional-grade documentation. The challenges are rarely technical capability. They're more often about sustained access to equipment, ongoing technical support when problems arise, and integration of documentation into decision-making processes that communities can influence.

Comments